“Pricing Power” has become a household term in the last couple of years, as the importance of pricing was revealed and elevated in every corner of the economy. It has also become, unhelpfully, a bit of a loose buzzword that can become limiting and rather … disempowering.

2023 and beyond will require a better understanding of what “pricing power” actually means for your specific company (what would you say right now?)

The existing “definitions” of “pricing power” can be conflicting, too narrow, too vague, or open to subjective, shifting interpretations. In the longer term, each may fail to do justice to firms’ need to maximize what pricing has “the power to do” for them.

Clarifying what “pricing power” is or isn’t

To have a useful definition of pricing power, it’s important to be clear on several points:

- Is pricing power a concept narrowly applicable to raising prices only? If yes, do we understand what service or disservice such a narrow view may do to our strategy, culture, and pricing optimization?

- Is pricing power an attribute of a company, or about a specific product, or both? What kind of entities can have / exhibit / contribute pricing power?

- How / in what quantity or metric do we quantify / compare / make relative statements about pricing power? (compare to “earning power”, or “computing power”)

- Is pricing power an established KPI or term with an authoritative definition that nearly everyone understands the same way, or a popular buzzword that we are free to use as each of us finds convenient (including changing what we want it to mean from one year to the next)?

- Would a product that’s neither highly differentiated, nor essential, never command pricing power? Or can “any” product provide pricing power if the supply/demand balance moves in its favor?

- What time period does pricing power refer to / is it measured over? Is it backward-looking or forward-looking? Or time doesn’t matter because pricing power once had, never changes?

- Is “pricing power” just a folksy, media-friendly way of saying price-inelastic demand?

Language matters, especially when it seeks to define strategy objectives. It can unite, divide, empower or confuse. When we make choices about what is associated with any “power” and by extension what is not, we influence our own thinking, the direction our teams believe in, and can unwittingly set ourselves up for groupthink.

Example: Warren Buffett’s attributed “definition” is way too narrow

Many adopted the famous conclusion from Mr. Buffett (us included) as a helpful endorsement of the power of pricing.

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power.”

I later learned Mr. Buffett’s full quote. It is quite narrow in its “definition” of pricing power, and I doubt he would stand by this being an actual definition (rather than an answer to a specific situation & question about a specific company, that has since been taken out of context):

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by a tenth of a cent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

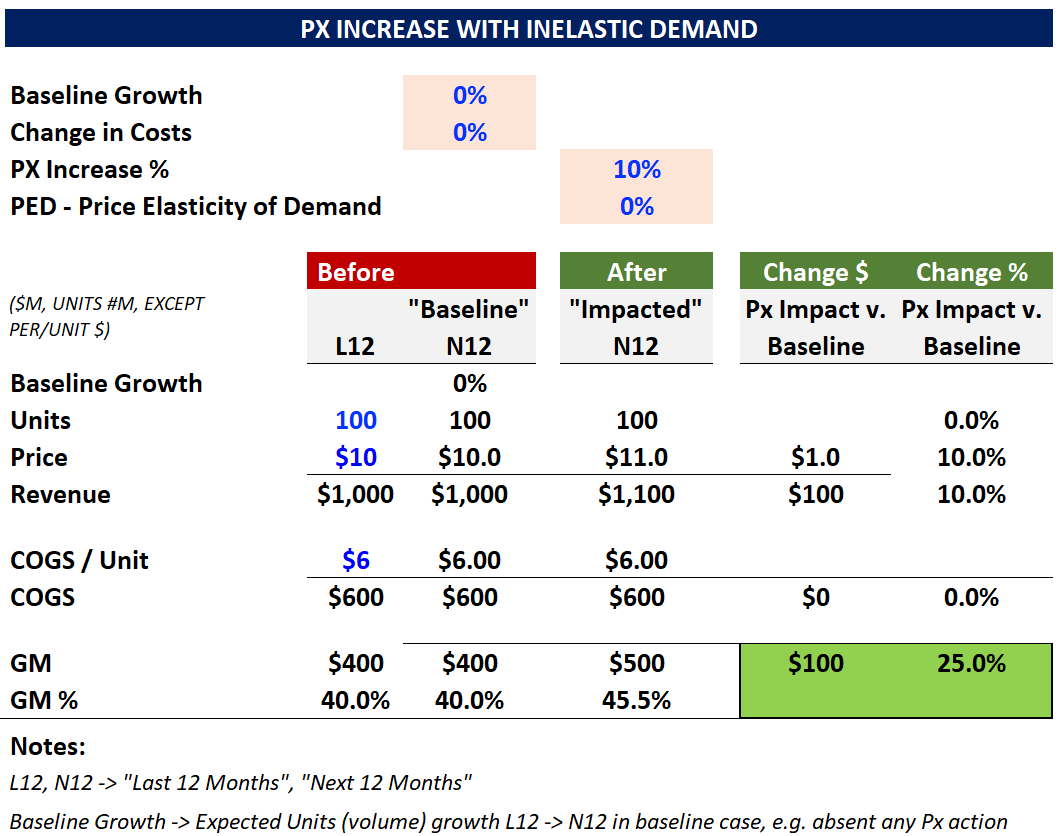

How many businesses keep 100% of their customers after a price increase (or even without a price increase!), and is it useful to think that only that select subset has “pricing power”? We’d call this the “narrow ideal” as illustrated below, with huge profit payoff and no cons. But if business was this simple, everyone could be CEO (or surely Head of Pricing!).

What if a price increase loses “some” business to competitors (for example, customers who were unprofitable to begin with, or customers amounting to low enough volume), would that mean you don’t have pricing power? Doubt Mr. Buffett meant that! If you lose 5% of volume to competitors but double your profits, would that make you less than a “very good business”? Hopefully we can agree this lens is too narrow to do justice to pricing power.

Conflating “pricing power” with “price increases” can prove risky (and limiting) in 2023 and beyond

For much of the last two years, conflating “pricing power” with “power to raise prices and come out ahead” would have been a good reflexive survival strategy. This is a good example of “thinking fast” that nearly all of us have evolved to survive fast-moving threats (about to be run over by a bus, or about to watch our company go under when input costs double or triple in a matter of weeks).

Firms faced in 2021-2022 this very kind of fast-moving threats in an abnormal environment. Cost pressures and supply chain failures not seen for decades drove favorable conditions (and even necessity) for pricing increases in many parts of the economy (and in most global economies). This perfect storm took many firms down a much needed re-learning of basics: that price increases should always be on the table of options and firms should invest in pricing capabilities that speed up assessment and harvesting of customers’ willingness to pay (WTP). The impact on profitability and the quickly achieved proof that price increases could mitigate the fast-moving cost threats resulted in a renewed and much needed appreciation for what was there all along: pricing’s importance in driving profitability.

However, as Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast And Slow” explains, oversimplifying and acting on a heuristic, can result in consistently biased, irrational, and ultimately counterproductive “laziness” that skips the necessary “slow thinking” we need to solve analytical, probability-dependent, multifaceted problems. Driving profitability with pricing and offering design is precisely that kind of problem. Narrowly conflating “pricing power” with “power to increase prices” is, under all but the most “emergency” scenarios, precisely that kind of risky heuristic.

The danger for 2023 and beyond is that firms get so seduced by the fast acting “drug” of price increases that they:

- Start preferring the “quick relief” drug to any appreciation of health itself (here, the much broader toolset of pricing strategy, offering design, etc).

- Become “addicted” to overuse of the drug to “compensate” for problems the drug is ill-suited to address (under-insured risks, for example).

- Self medicate and overestimate their relationships (customers’) tolerance, while underestimating the importance of proper timing, dosage and execution.

- Let a “bias for action” to harvest WTP with value-based pricing (healthy mindset) morph into “bias for inaction” to skip all the required steps and analysis as to whether WTP is in fact there (“thinking slow”) …

- (Worst-case outcome) Lose the urgency to create more customer value worth higher WTP. It can be seductive to conclude from a successful price increase that the firm is already putting out “enough” value (“see? we can ask more from our customers for what we already produce!”). But absent incremental deliveries of new products and value to customers, firms will find out that pricing power is a rapidly depleting asset.

What do you think? Does your company talk about “pricing power” in 2023, and what does it mean to you?

————————————————————-

In Part 2 – Redefining “Pricing Power” Both Broadly Enough, and Precisely Enough we will present:

- Our proposed “table stakes definition”

- An “advanced” proposed definition that seeks to add time-specificity and ability to “compare” pricing power on a standardized basis

- Some of the existing definitions we found, as context for the questions we raised above and for you to choose what works for you.

In Part 3 – Pricing Power for Consumer Brands in 2023, we will share 5 ways Consumer Brands can get both broader and more intentional nurturing, harvesting and measuring Pricing Power, in our 2023 context.

In Part 4 – Pricing Power for Saas & Software firms in 2023, we will bring the lens on unique features of SaaS & Software pricing and 5 ways they too should focus on Pricing Power in 2023.

Please don’t forget to hit the “Subscribe” button.

To get in touch with us, visit www.ebitdacatalyst.com.