Keurig’s Pricing Strategy vs Low-Priced Ground Coffee

What is Keurig’s Pricing Strategy to fend off ground coffee from cannibalizing its cash cow K-Cups? 1. The price of reassurance “You can always easily go back to ground coffee”

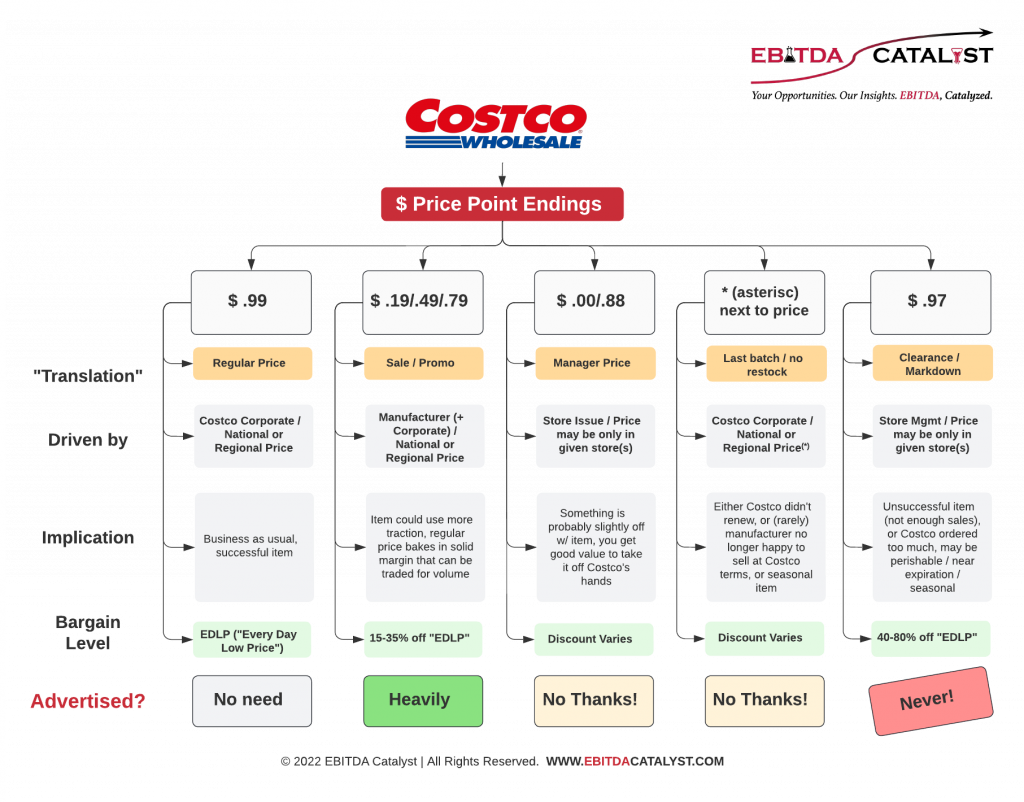

Most consumers don’t know that Costco uses a “secret code” of price endings to communicate (though some astute shoppers and reporters have figured this out long ago). Did you know that prices ending in .97 signal clearance, deep markdown, and generally a bargain even by Costco’s very bargain-focused standards (sometimes as much 60-80% off Costco’s “normal” price)? Did you know that on any given day in any given store you may find a few dozen such clearance prices, spread throughout the store?

If you’re a typical consumer shopping at Costco primarily because of “unbeatable prices” … it pays to know Costco will occasionally take even those prices down. Training that 6th or 7th sense on the quick cheatsheet below will pay dividends for the pocketbook, and maybe even impressing the neighbors as they complain of yet another pocket-punishing trip to the regular grocery store.

If you are in the pricing or brand strategy profession, however, you would likely notice some seemingly strange and “different” ways Costco goes about this business … and ask a lot of “Why?” questions.

This seems highly counter-intuitive. Costco’s other sales are often advertised way in advance through its ubiquitous coupon books, emails. Then of course, once in store, those sales items are typically in prominent end-of-aisle locations, with price signs using phosphorescent green highlighter to make sure they’re easy to find. The customer is visually triggered, with the signs designed to elicit a nearly Pavlovian response (often successful!), driving both purchases and store traffic patterns. Basically, what you’d expect from a retailer that decided to use a promo (for a limited time) to move a lot of volume and generate a lot of brand awareness for the manufacturer of the item in question. This is great price execution, but so far not necessarily different from other top-flight retailers.

The .97 items, by contrast, take a sharp eye and focus to find. Were it not for .97 signal, only people who memorize prices, pay attention to comparable items one shelf over, or have an outsized mental map of what countless items “generally cost / should cost” could detect there is even a bargain there. Does Costco not really want to move these items priced super-low and ending in .97, or what?

Sure they do. They’d just like the least amount of fanfare and awareness and behavioral impact while doing so … a bit of a hush-hush “bury the not-on-message sales” operation of sorts. This is brilliant brand management through price strategy through price execution in its own right!

Let’s consider what Costco’s brand strives to stand for, and what the items carrying the .97 price point could do that brand image and consistency (and Costco’s pricing prowess / customers’ willingness to pay).

I’d guess these are both on Costco’s messaging list and on most of its shoppers’ mind:

Let’s start with that very hush-hush bargain … the 97 cents clearance item. To see why Costco’s “unorthodox” practice of not advertising such clearance sales at all is in fact brilliant, let’s imagine the opposite. There would be a corner of each Costco warehouse (or even better real estate) dedicated to CLEARANCE. There would be signage all over that area making it impossible to miss (like they do with the 49 cents and 79 cents sales, but maybe even more distinctly marked). Customers who shop at that specific store may even get, when possible (remember this is a store-level price decision, and it is often not consistent with long advance notice), emails reminding them to “get them while they last” for the doomed items (but such emails would need to be clear that those prices are only available at Store X).

Note: I recognize the majority of shoppers may not care or think about the items below at all … they would just be happy with the lower prices and move on without additional “inferences”. However over time, whether explicit inferences are made by more sophisticated shoppers, or behaviors are formed by less sophisticated ones

Store shoppers may infer, or worse, develop habits based on inferring that:

In effect, any such inference would be diluting Costco’s intended brand image. Note that some of these inferences might well be wrong in specific situations … for example the items may be sold at a loss, as deep markdowns can be, so the discount doesn’t necessarily imply the margins in the regular price were THAT fat! But Costco is unable to educate every customer … In fairness to Costco, not even the best merchandising team should be expected to have a 100% batting average with every product selling through all the time.

Customers’ perceived value drives willingness to pay (WTP)… and Costco’s money is made from customers whose perceptions support WTP both for the “regular price” merchandise, and for the all-important membership fee, paid precisely because “regular price” at Costco is believed (in many, but not all cases, accurately) to be “unbeatable prices” compared to everywhere else. By NOT advertising these Clearance sales, Costco may make a small sacrifice in the very few cases where not enough shoppers notice the bargain prices / nearly unbelievable comparisons with competitor products nearby. It may end up with some unsold inventory, and for perishable items that means a full loss of COGS. But that is peanuts in dollar terms against the giant value Costco drives by preserving the WTP for its “regular priced” items untarnished from the “undesirable” 97 cent fallout.

It may appear at first blush that Costco’s actions in these two situations contradict themselves, and can’t both be consistent with its brand message. But they are both examples of excellent price execution. The motives and more importantly the “sponsor” for the cost of each type of sale are quite different, and warrant the different (indeed, opposite) treatment in messaging.

For the “regular sales”, it is usually safe to assume:

The one thing that carries over from the 97 cent situation is the (warranted) inference that there is enough margin in the product to still make a bit of money or break even at the discounted price. But recall from our chart that discounts here are much less than in the 97 cent situation, so that inference would be less alarming … and of course recall our caveat that few shoppers walk around thinking about Costco’s margins!

These “regular sales” then, leave the consumer with intact confidence in items 1-4 of Costco’s brand message we outlined above. Promoting them makes both pricing strategy, and brand strategy sense!

Understanding Costco’s messaging code embedded in its price point endings can be dramatically useful for consumers looking for bargains and further inflation-fighting opportunities. For pricers and marketers, it invites admiration and respect for a brand that is immensely successful because it thinks the details through. When seeing Costco do something differently, if it doesn’t immediately seem clear why, chances are they’ve figured something out before the rest of us, rather than the other way around.

Final caveat: There are exceptions to some of the price point ending “rules” above. For example, sometimes a “regular” sale price can also end with a 99 cent, as you can see in the images above. While some of the ideas above are based on a limited sample of observations, I would welcome and incorporate comments from Costco if any of the facts above can be improved with source information.

What is Keurig’s Pricing Strategy to fend off ground coffee from cannibalizing its cash cow K-Cups? 1. The price of reassurance “You can always easily go back to ground coffee”

Disney’s new motto: getting you and your kids to watch ads … priceless. Disney+ will serve up some expensive pricing magic … again. The economics of streaming services are increasingly

Note: A version of this article about insurance premium increases appeared in our LinkedIn newsletter, Pricing Power Clarity®. Trust Buffett, it’s a great business It’s no wonder Warren Buffett loves